Furness Railway

Connecting up

The first few years of the Furness Railway were modest but the success of the line and the scope for expansion encouraged grand visions for the future.

The Furness Railway was a merger of two schemes – to take iron ore from Dalton and slate from Kirkby to the port of Barrow. Furness mine owners were interested but so, crucially, were the Dukes of Devonshire and Buccleuch. They owned most of Furness and as landlords they received a levy on each ton of ore raised. It was therefore in their interest to stimulate iron mining. One thing to remember about the Furness Railway was that it was a small venture, self-contained within Furness.

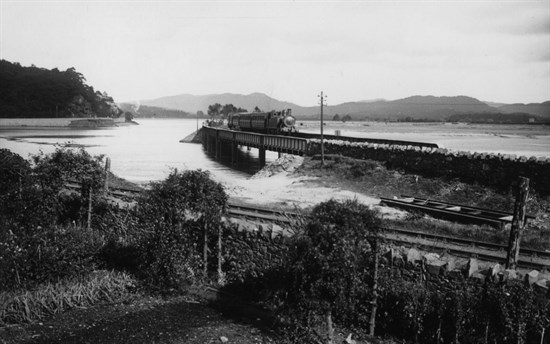

For its first few years the Furness Railway’s future was uncertain and expansion only modest – to Lindal in 1851, to Ulverston in 1854. A permanent link with the outside world came only in 1857 when the Brogdens built the Kent and Leven viaducts. A few years later the Furness Railway took over this Ulverston to Lancaster line, a crucial development in the growth of Barrow.

Two men were to prove to be instrumental in changing the Furness Railway into much more than just a railway: James Ramsden and the Duke of Devonshire. James Ramsden came to Barrow in 1846 as the company's locomotive superintendent and eventually retired as managing director. William Cavendish, the 7th Duke of Devonshire, was the money behind the Furness Railway, docks, steelworks and juteworks. His main estate was at Chatsworth in Derbyshire and he was closely linked with the development of Buxton and Eastbourne. However, his fondness for Holker Hall, in South Lakes, and his sense of paternal responsibility meant that he took a strong interest in the new town he had in effect financed.

An Engine for Growth

The Furness Railway didn't just build a railway line but their vision for Barrow was that it come to rival Liverpool.

James Ramsden and the Duke of Devonshire didn't see the Furness Railway as just a simple iron ore and slate transporation line. They thought that by using the same model of large-scale investment they could create similarly profitable enterprises. One day, the thinking went, Barrow could rival the likes of Liverpool.

With that in mind, when in 1854 the Hindpool estate of the late John Cranke came onto the market, the Furness Railway showed an immediate interest. The estate comprised 160 acres, which the Railway secured in August 1854 for a price of £7,000. This purchase was to prove key to Barrow’s subsequent expansion. It allowed for large-scale industrial development.

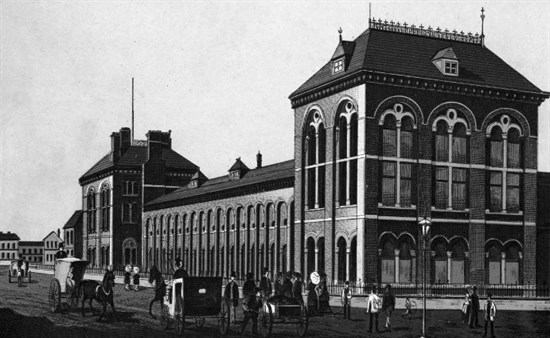

In October 1859 the ironworks were first put into blast by its owners Hannay and Schneider. Using the vast reserves of iron ore recently found at Park mine it made perfect sense for iron to be produced locally rather than being transported away. Soon Ramsden was suggesting that a steelworks (pictured left) should be also commence and the Duke of Devonshire was again happy to invest in such a logical next step.

Concurrently, a docks project was set up. The capital for the docks project, originally £137,000, was raised principally from the Duke of Devonshire and the Duke of Buccleuch, after whom the first two docks were to be named. The railway company bought up the land around the Channel, including the whole of Barrow Island and, on the mainland side. Work started in 1865, at first on what was to become the Devonshire Dock, at the northern end of the Channel. It was a massive project, taking more than two years to complete and at its height employing 2,000 men in its construction. However, the docks never repaid the expense they incurred and loan payments were a severe drain on the Furness Railway finances.

Victorian Barrow

Barrow was a smoky, noisy, bustling town of 45,000 just twenty years after the dock construction started and the steelworks set up. This phenomenal growth was the result of active recruitment by the town’s industrial syndicate and it created a "melting pot” community drawn from all over the country.

Some came from the neighbouring counties of Cumberland and Westmorland, from the rest of Lancashire and nearby Yorkshire. A group of railway workers migrated along the Furness Railway line from Lancaster to form a small colony at Roa. From further afield came Scots, to work as engineers and furnacemen at Hindpool, jute workers from Dundee and shipyard workers from the Clyde. Irish navvies were brought to Barrow to build the docks and later Belfast men were employed at the shipyard.

Thousands of workers flooding into Barrow in the 1860s and 1870s needed to be housed. There was no municipal programme of housing and private builders on their own couldn’t cope with the demand. The solution was for the major industries to contract building companies to erect flats and houses, which the companies owned and rented out to their workers. For some twenty years, approximately 1865-1885, the town must have resembled one giant building lot.

By 1866 the new town of Barrow had outstripped its old guardian Dalton and after pressure from leading citizens a Royal Commission inquiry agreed to set Barrow free to form its own municipality. The first Town Council was nominated in 1867 by the Duke of Devonshire (elections began the following year), and the first Mayor was James Ramsden, who twenty years earlier had supervised the first hesitant steps of the Furness Railway.

Organised sport began in Barrow in the 1870s. The two main sports were rugby and cricket, with both town teams sharing facilities at Cavendish Park on Barrow Island. Other sports popular in the 1870s and 1880s were rowing in Walney Channel, athletics and cycling at Cavendish Park and golf on Walney provided by the Furness Golf Club. Sporting activities gave the town an identity, welded communities together and made productive use of rare leisure time.

End of the Line

By the time Ramsden died in 1896, the Sheffield steel firm Vickers were negotiating to purchase the relatively new Barrow shipyard and the town’s second life was beginning. When Vickers came to Barrow in 1896 the shipyard employed 5,500; by 1910 the number of workers had increased to 10,500. The increase in workforce, and the need to attract and retain skilled workers, brought an immediate problem for Vickers – where to house them? A permanent solution came with the building of 950 houses in two estates at Vickerstown on Walney Island, built and finished off from 1899 to 1904.

For a few years the only way to reach work for Vickerstown men was by ferry. A proposed Walney Bridge was championed by Vickers and opposed by the Furness Railway, who operated a by-now profitable ferry. After a town poll it was decided to build the bridge, paid for by Vickers, the Council and Government grants. Its opening in July 1908 was a symbolic moment. Power was seen to have shifted from the Furness Railway, who were no longer the company behind the company town.

Furness Railway ceased to exist in 1922 when it was absorbed into the London, Midland and Scottish Railways in a Government programme to decrease what it saw as wastefulness and inefficiency of having more than one hundred railway companies in Britain.